Education & Advisory Services

Becoming THE I’m Still Here® Center of Excellence Model Community

When developing Abe’s Garden Memory Support, our team toured care communities considered to be the top in the country to identify many of the best practices at the time. It was then that we discovered the world-renowned memory support and engagement consultancy Hearthstone Institute and their evidence-based I’m Still Here® approach to dementia care.

Prior to opening our doors in 2015, our staff was educated in the I’m Still Here® approach, and after completing this training, our organization became a certified Memory Support Center of Excellence – and we have recertified every year since.

In September 2022, the Education and Advisory Division of Hearthstone Institute merged into Abe’s Garden Community, forming the Hearthstone Institute at Abe’s Garden (HIAG). Now, we are combining our collective knowledge, influence, missions, and resources to continue expanding, improving, and sharing cutting-edge best practices in older adult care.

Abe’s Garden Community is now THE Center of Excellence model for professionals from senior living communities to experience and be educated in the I’m Still Here® approach.

What is the I’m Still Here® approach?

This approach utilizes research-based, non-pharmacologic approaches to treat the agitation, aggression, apathy, and anxiety that individuals living with dementia often experience.

I’m Still Here® combines meaningful activities, specialized communication techniques, and an enriched environment to provide engagement, choice, and true purpose regardless of the level of cognitive challenge. Residents are invited to participate in a variety of programs tailored to their interests, needs, and abilities to empower and encourage them to continue to learn and socialize.

Additionally, I’m Still Here® increases levels of self-confidence, significance, and well-being by creating opportunities for residents to express their preferences and choices.

This philosophy empowers individuals with cognitive challenges to discover activities of interest. This might encourage socializing or participation in purposeful activities.

Our Unique Approach to Dementia Education

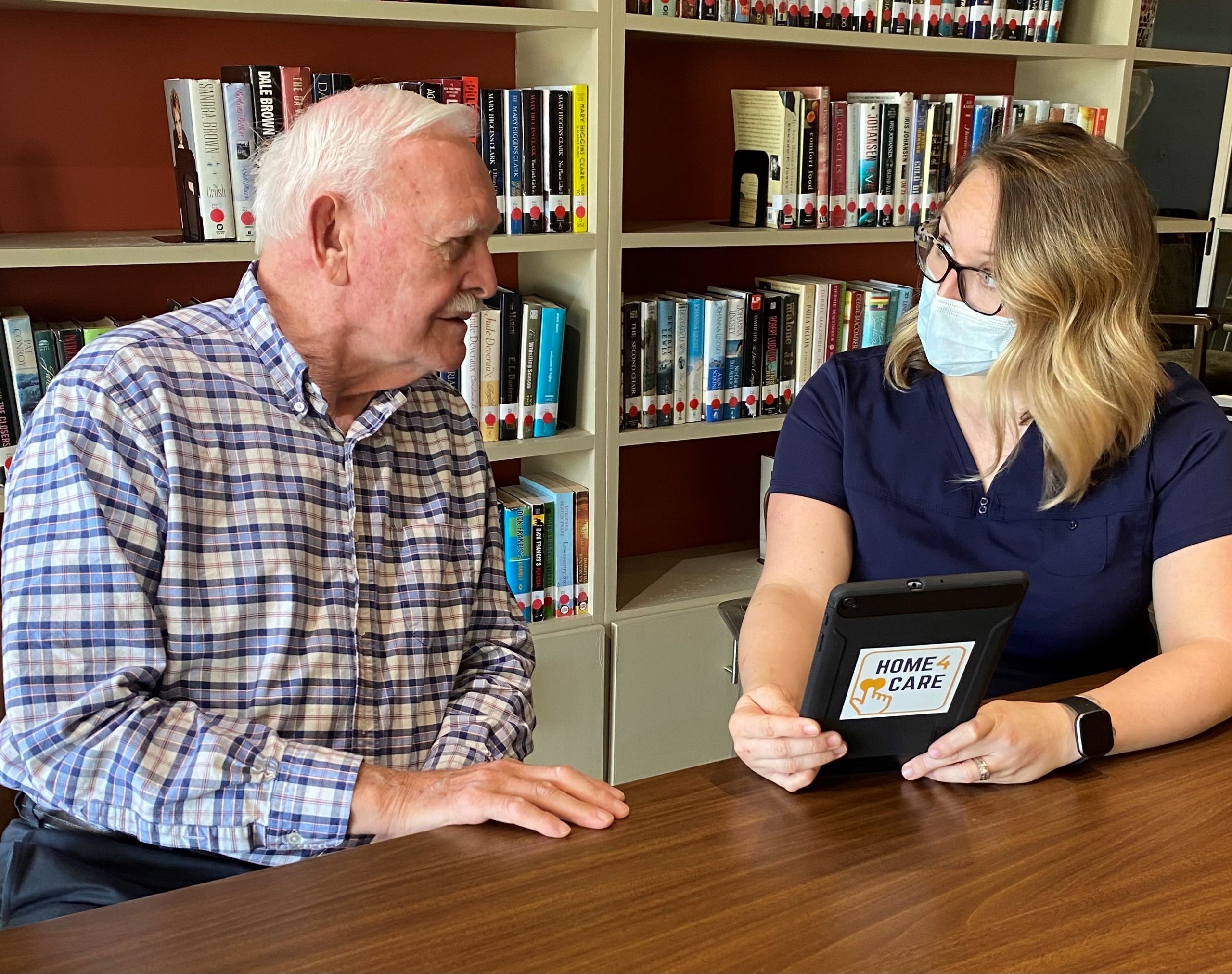

Hearthstone Institute at Abe’s Garden provides education and evidence-based best practices to care partners serving residents with all levels of cognitive challenges.

Our mission is to help our clients and partners create “A Life Worth Living” for people living with dementia by enriching their lives and offering hope.

What Makes the Hearthstone Institute at Abe’s Garden Different?

We have over 25 years of hands-on experience caring for people living with dementia and educating staff on dementia care best practices.

HIAG team members have extensive experience in operations and industry best practices, many of which were first pioneered at Hearthstone Institute’s Alzheimer’s care residences.

Our approach is evidence-based. Our education modules and engagement materials are backed by empirical research, data, and outcomes.

Best-in-class education allows memory care communities to keep residents authentically engaged regardless of the severity of their dementia, thereby increasing staff job satisfaction and loyalty.

Centers of Excellence, Improving Dementia Care Across the Country

With more than 20 Centers of Excellence nationwide and counting, Abe’s Garden Community is the model and educational hub for certification.